- August 18, 2023

Program Notes for Voices of Light

PROGRAM NOTES: VOICES OF LIGHT

PROGRAM NOTES: VOICES OF LIGHT

BY RICHARD EINHORN

Imagine walking down an ordinary street in an ordinary city on an ordinary day. You turn the corner and suddenly without warning, you find yourself staring at the Taj Mahal. It was with that same sense of utter amazement and wonder that I watched Carl Dreyer’s THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC for the first time.

That was back in January of 1988. I was idly poking around in the film archives of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, looking at short avant-garde films, when I happened across a still from JOAN OF ARC in the silent film catalog. In spite of a deep love of cinema and its history, I had never heard of either the director or the film, but since my friend Galen Brandt had suggested that I do a piece about Joan of Arc at some point, I asked to take a look at it. Some 81 minutes later, I walked out of the screening room shattered, having unexpectedly seen one of the most extraordinary works of art that I know. I immediately began to plan the piece about Joan of Arc that my friend had suggested.

In early 1993, Bob Cilman of the Northampton Arts Council agreed to present VOICES OF LIGHT and I wrote the entire score in about 3 1/2 months. In February of 1994, VOICES OF LIGHT premiered to sold–out crowds at the Academy of Music in Northampton, Massachusetts, performed by the Arcadia Players and conducted by Margaret Irwin–Brandon. Since then, the piece has been performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music Next Wave Festival and elsewhere. A CD featuring the medieval vocal group Anonymous 4 and the Radio Netherlands Philharmonic and Choir conducted by Steven Mercurio was released in October of 1995 on Sony Classical.

VOICES OF LIGHT is a meditation on the life and personality of Joan of Arc. It is scored for soloists, chorus, orchestra, and one very special bell (about which more later). The libretto is a montage of ancient writings, assembled primarily from female medieval mystics including Joan of Arc herself. The “staging” of the work is a screening of THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC. The piece explores the patchwork of emotions and thoughts that are stitched together into the notion of a female hero. Such a hero invariably transgresses the conventions and restrictions her society imposes. And Joan of Arc –– the illiterate teenage peasant girl who led an army, the transvestite witch who became a saint –– Joan of Arc transgressed them all.

ABOUT JOAN OF ARC:

Joan of Arc was deeply religious, utterly chaste, and astonishingly brave in the face of horrific abuse. She certainly deserves the sainthood the Church bestowed upon her. But Joan challenges the very meaning of holiness. True, this image of the virginal shepherd girl called to a divine mission by angels is part of her story, but it is only one part.

- Registre du parlement de Paris. Pge 24 – Archives Nationales. The only known contemporary portrait of Jeanne d’Arc

It seems to clash with the fact that her closest companions were brutal soldiers with names like The Bastard of Orleans or La Hire (The Rage). It seems impossible that another of Joan’s close intimates was Gilles de Rais, the infamous “Bluebeard” who was burned at the stake for the serial murder of young boys. And the humble pious image simply cannot accommodate a woman who, when asked about one of her childhood neighbors, a man who sympathized with her enemies, responded that she would cut his head off (“God willing,” of course).

She was born in about 1412 in Domremy, France, a tiny farming village in the Meuse Valley. When Joan was thirteen or so, she began to hear voices. At seventeen, her voices told her that she had been given a divine mission to reunite France. At the time, in the middle of the Hundred Years’ War, much of France was in the hands of the hated English and their Burgundian allies. Charles, the uncrowned king or dauphin, was in exile and his path to Reims, where all the kings of France had been crowned since time immemorial, was blocked by the English troops. Orleans, a city that lay in a strategically important area of the strife, had been besieged for over a year and had begun to weaken.

Spurred on by her voices, Joan implored Robert de Baudricourt, the governor of nearby Vaucouleurs, to permit her to travel to Charles’s court at Chinon. Initially reluctant, even incredulous, Baudricourt finally granted the permission and Joan, “borrowing” some men’s clothing to disguise herself during the journey, left with two friends for the court of the uncrowned king.

Joan’s powers of persuasion must have been remarkable. She managed not only to arrange an audience with Charles but also to convince him she should travel with an army to help lift the siege of Orleans. Within days of her arrival, the French army, with Joan’s active participation, had destroyed the besieging English forces, a turning point in the war. Although seriously wounded, Joan helped lead the final successful assault on the Tourelles, the English garrison, an attack that resulted in the deaths of two of England’s most important military commanders.

With Orleans secure, Joan and the army cleared a path to Reims for the coronation, recapturing numerous towns along the way. Joan was so feared by the English and their Burgundian allies that the mere announcement of her presence outside the walls of a town would elicit a quick surrender. Charles VII was crowned in Reims on July 17, 1429, with Joan of Arc by his side. It had been less than seven months since she had left her farm village, and Joan was seventeen years old.

For about a year or so, Joan was a mercenary knight, fighting (and winning) numerous battles. However, after she failed to take Paris in September of 1429, her fortunes began to wane, and in May of 1430, outside the walls of Compiègne, she was dragged from her horse by a Burgundian archer and captured. She was subsequently sold to the English and transported to Rouen, where the English and the Burgundians had arranged for a court of the Inquisition to try her for heresy. The trial’s purpose was not only to discredit her among her people (as she was already a legend in France), but also to cast doubt on the legitimacy of the king whom she had helped to crown. While in prison, Joan refused to give up her male clothes, was kept in a tiny cell and was always in chains (she had tried to escape earlier in her captivity by leaping from the turret of a castle).

In Rouen, arraigned before a panel of learned judges, priests, and lawyers, Joan was questioned repeatedly about her voices, her male dress, and her sense of her mission. After months of resistance which left her ill and exhausted, Joan was dragged out into a courtyard of the church of St. Ouen and publicly coerced into signing a statement of adjuration in which she denied that her voices were from God. She was sentenced to life imprisonment and her head was shaved. Three days later, however, she retracted her abjuration and affirmed that her voices were divine. She was promptly excommunicated for heresy and burnt on May 30, 1431. Joan of Arc was nineteen years old when she died.

Twenty-five years later, Charles VII and Joan’s mother, Isabelle Romée, petitioned the pope to restore her to the Church. Many of the women and men who knew Joan from Domremy and from her career as a solider were interviewed. These transcripts (which, like the trial transcripts, have survived) provide substantial corroboration for a story that would otherwise seem unbelievable. In 1920, nearly 500 years after her death, Joan was declared a saint, the only saint who was first excommunicated and burned.

Joan’s refusal to conform to our normal categories of behaviors creates many apparent paradoxes and contradictions. Yes, she was a great warrior, but she was also a pious mystic who would halt her soldiers simply to listen to church bells. She was an illiterate farm girl, but she had no problem consorting with royalty. Although she was the most practical and skeptical of leaders –– she had quite a reputation for debunking fraudulent prophets –– she heard voices that today would probably earn her a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia.

Her powerful, complex personality has attracted an amazingly disparate group of admirers over the years, from George Bernard Shaw to Andrea Dworkin, to name just a few. She is a beloved Catholic saint and a hero for many young girls, regardless of their religious background. But in the course of my research, I also met with members of covens who worshipped Joan as a great witch. In the United States and England, numerous feminist and lesbian authors have written eloquently on Joan of Arc. Meanwhile, in France, her role as the supreme symbol of French nationalism has been co-opted by the extreme right wing. And, of course, Joan embodies the romantic myth of the misunderstood, uncompromising artist: true to her/his inner voice until death.

CARL DREYER’S “THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC”:

The strange history of THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC (1928) nearly equals Joan’s itself. It has many of the same elements, including obsession, madness, and even fire.

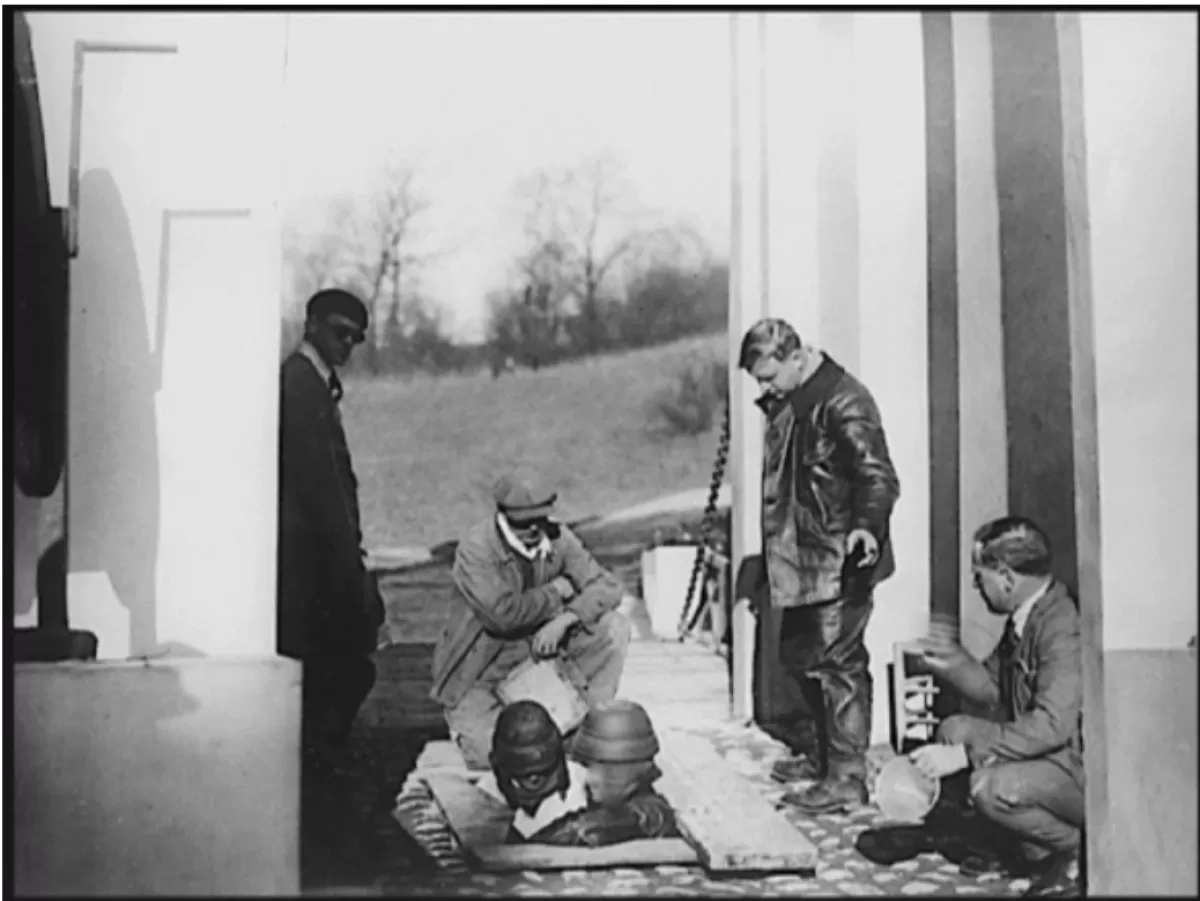

Carl Dreyer on set for The Passion of Joan of Arc

THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC was the next film made by Société Générale, the studio that had produced Abel Gance’s NAPOLEON. In fact, Dreyer himself was on the set of the Gance film and used many members of the technical crew and several of the actors (notably Antonin Artaud, the stunningly handsome enfant terrible of the avant-garde theater, who was later incarcerated in a mental institution). The original screenplay for JOAN was by Joseph Delteil, who had written a rather hyperventilated book about her. For one reason or another, Dreyer chose to forgo most of Delteil’s ideas and instead used actual excerpts from the trial transcripts as the script (the film, which is set entirely at Joan’s trials, and burning, compresses the action of the trial from seven months into a single day).

To portray Joan of Arc, Dreyer cast against type Renée Falconetti, a leading member of the Comédie-Français. Rumors abound about the excruciating ordeal Falconetti suffered during the shoot: when her head was shaved for the final sequence of the film, apparently the entire crew wept for her and she broke down; the shooting ground to a halt while she recovered.

The film, censored somewhat by the Catholic Church prior to its release, was soon hailed as one of the greatest films of all time. Falconetti’s performance was (and is) considered one of the most extraordinary ever filmed. With its extreme close-ups and bizarre camera angles, with an editing rhythm that breaks nearly every rule of the craft, THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC makes virtually every movie critic and scholar’s short list of masterpieces. It clearly influenced such filmmakers as Bergman, Fellini, and Hitchcock, and echoes of its intense style appear in the work of such contemporary masters as Martin Scorsese. Shot without makeup and with “natural” acting, JOAN looks like it was finished yesterday.

But a few months after the premiere, Joan’s judges descended upon Dreyer’s film. The negative and virtually all prints of THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC were destroyed in a warehouse fire. Dreyer, referring in all likelihood to his workprint for the original cut, painstakingly reconstructed the entire film from outtake footage that had survived the fire. This second version was destroyed in a second fire! Devastated, Dreyer gave up and moved on to his next film, VAMPYR.

From here the history of the film becomes confusing. Highly corrupt prints that somehow managed to survive the fires circulated for a while. In addition, the Cinémathèque Français unearthed a copy of the film in its vaults (at the time, it was unclear which version it was). In the late forties and early fifties, a French film historian by the name of Lo Duca pieced together his version of the film (apparently using prints from both versions) and added a score that was a montage of Albinoni, Vivaldi, and other Baroque composers. The result so horrified Dreyer that he completely disowned the “Lo Duca” version.

Then, in 1981, several film cans from the ‘20s were discovered at a mental institution in Oslo, Norway, stashed in the back of a closet. They were shipped, unopened to the Norwegian Film Institute. Inside the cans, in nearly perfect condition, was a copy of THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC with Danish intertitles. The accompanying shipping information made it clear that it was, in fact, a print of the original version of Dreyer’s great film.

VOICES OF LIGHT:

THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC was an inspiration for VOICES OF LIGHT, but my goal was to attempt a stand-alone work that would speak to various aspects of Joan’s life and legend.

Richard Einhorn and Voices of Light / The Passion of Joan of Arc

As I was developing the piece, I recalled my studies of medieval musical practice, in particular the multi–lingual motets that I love to listen to. The notion of a work of art with simultaneous layers of text struck me as a medieval idea that was also delightfully modern as well.

Since Joan heard voices, I knew the work would have singing, but what would everyone sing? I did a considerable amount of research into the history of Joan’s life and persona and began to explore the rich body of literature written by female mystics from the Middle Ages. I decided to create a libretto that would consist primarily of excerpts from these writings, chosen for their beauty as literature and also for their relevance to themes in Joan’s life. In addition, I decided that all the words sung in the score would be in ancient languages (Latin, Old and Middle French, and Italian).

A brief example: Although the Inquisitors did not physically harm Joan, she was shown the instruments of torture. I thought that, rather than speak directly about this horror, it might be more interesting to explore some of the stranger aspects of the medieval view of physical pain, the tradition of suffering as a means of achieving spiritual ecstasy. Accordingly, the chorus obsessively repeats the phrase “glorious wounds” while a solo soprano sings a combination of lurid texts from both Blessed Angela and Na Prous Boneta, a 13th-century penitent and 14th-century heretic, respectively.

I didn’t want to have any characters in a conventional sense, but after reading Joan of Arc’s military correspondence (although illiterate, Joan dictated her letters to a scribe), I decided that I wanted her to make an appearance in my piece, singing excerpts from her letters as well as some other texts that she either certainly said or could have said. Since no one knows what Joan looked like, I decided that no one would know much about her singing voice: accordingly, Joan’s “character” is sung neither in a soprano nor alto range, but in both simultaneously, with simple harmony and in rhythmic unison.

Just prior to writing VOICES OF LIGHT, I traveled to France to visit some of the important Joan of Arc historical sites. I went to Orleans where she won her first battle and also to Rouen, where I was deeply moved by the ruins of the castles where Joan was held and the cross erected at the site of her martyrdom. I also traveled to the little village of Domremy, Joan’s birthplace in the southeast, where her house and church, much restored, still stand. I took along a portable DAT recorder and recorded the sound of the Domremy church bell and later incorporated it into my score. I felt that Joan, who so loved church bells, whose voices seemed to speak to her whenever they were ringing, would appreciate the effort.

AN EXPERIENCE YOU WON’T FORGET

Join Pacific Chorale on October 7, 2023 to see this captivating concert! Tickets start at $28, learn more here.